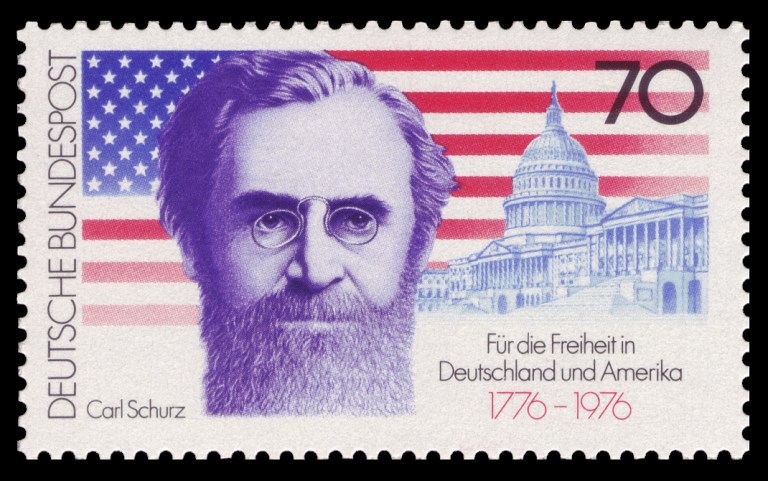

Carl Christian Schurz

Another Envelope was created by the Tricentennial Foundation for Carl Christian Schurz, of whom Wikipedia knows: (March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906), who was a German revolutionary, American statesman and reformer, U.S. Minister to Spain, Union Army General in the American Civil War, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of the Interior. He was also an accomplished journalist, newspaper editor and orator, who in 1869 became the first German-born American elected to the United States Senate.

Carl Christian Schurz was born on March 2, 1829 in Liblar (now part of Erftstadt), in Rhenish Prussia, the son of Marianne (née Jussen), a public speaker and journalist, and Christian Schurz, a schoolteacher.

He studied at the Jesuit Gymnasium of Cologne, and learned piano under private instructors. Financial problems in his family obligated him to leave school a year early, without graduating. Later he graduated from the gymnasium by passing a special examination and then entered the University of Bonn.

During the 1849 military campaign in Palatinate and Baden, he joined the revolutionary army, fighting in several battles against the Prussian Army. Schurz was adjunct officer of the commander of the artillery, Fritz Anneke, who was accompanied on the campaign by his wife, Mathilde Franziska Anneke. The Annekes would later move to the U.S., where each became Republican Party supporters. Anneke’s brother, Emil Anneke, was a founder of the Republican party in Michigan. Fritz Anneke achieved the rank of colonel and became the commanding officer of the 34th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment during the Civil War; Mathilde Anneke contributed to both the abolitionist and suffrage movements of the United States.

When the revolutionary army was defeated at the fortress of Rastatt in 1849, Schurz was inside. Knowing that the Prussians intended to kill their prisoners, Schurz managed to escape and travelled to Zürich. In 1850, he returned secretly to Prussia. Schurz then went to Paris, but the police forced him to leave France on the eve of the coup d’état of 1851, and he migrated to London. Remaining there until August 1852, he made his living by teaching the German language.

While in London, Schurz married fellow revolutionary Johannes Ronge‘s sister-in-law, Margarethe Meyer, in July 1852 and then, like many other Forty-Eighters, emigrated to the United States. Living initially in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Schurzes moved to Watertown, Wisconsin, where Carl nurtured his interests in politics and Margarethe began her seminal work in early childhood education.

In Wisconsin, Schurz soon became immersed in the anti-slavery movement and in politics, joining the Republican Party. In 1857, he was an unsuccessful Republican candidate for lieutenant-governor. In the Illinois campaign of the next year between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, he took part as a speaker on behalf of Lincoln—mostly in German—which raised Lincoln’s popularity among German-American voters (though it should be remembered that Senators were not directly elected in 1858, the election being decided by the Illinois General Assembly).

In 1858, he was admitted to the Wisconsin bar and began to practice law in Milwaukee. In the state campaign of 1859, he made a speech attacking the Fugitive Slave Law, arguing for states’ rights. In Faneuil Hall, Boston, on April 18, 1859,he delivered an oration on “True Americanism,” which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of “nativism“. Wisconsin Germans unsuccessfully urged his nomination for governor in 1859. In the 1860 Republican National Convention, Schurz was spokesman of the delegation from Wisconsin, which voted for William H. Seward; despite this, Schurz was on the committee which brought Lincoln the news of his nomination.

In spite of Seward’s objection, grounded on Schurz’s European record as a revolutionary, after his election President Lincoln sent him in 1861 as minister to Spain, where he succeeded in quietly dissuading Spain from supporting the South.

During the American Civil War, Schurz served with distinction as a general in the Union Army. Persuading Lincoln to grant him a commission in the Union army, Schurz was commissioned brigadier general of Union volunteers in April 1862. In June, he took command of a division, first under John C. Frémont, and then in Franz Sigel‘s corps, with which he took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. He was promoted major general in 1863 and was assigned to lead a division in the XI Corps at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, both under General Oliver O. Howard. A bitter controversy began brewing between Schurz and Howard over the strategy employed at Chancellorsville, resulting in the routing of the XI Corps by the Confederate corps led by Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Two months later, the XI Corps again broke during the first day of Gettysburg. Containing several German-American units, the XI Corps performance during both battles was heavily criticized by the press, fueling anti-immigrant sentiments.

Following Gettysburg, Schurz’s division was deployed to Tennessee and participated in the Battle of Chattanooga. There he served with the future Senator Joseph B. Foraker, John Patterson Rea, and Luther Morris Buchwalter, brother to Morris Lyon Buchwalter. Senator Charles Sumner (R-MA) was a Congressional observer during the Chattanooga Campaign. Later, he was put in command of a Corps of Instruction at Nashville. He briefly returned to active service, where in the last months of the war when he was with Sherman‘s army in North Carolina as chief of staff of Henry Slocum‘s Army of Georgia. He resigned from the army after the war ended in April 1865.

In the summer of 1865, President Andrew Johnson sent Schurz through the South to study conditions; they then quarrelled because Schurz supported General Slocum’s order forbidding the organization of militia in Mississippi. Schurz’s report, suggesting the readmission of the states with complete rights and the investigation of the need of further legislation by a Congressional committee, was ignored by the President.

In 1866, Schurz moved to Detroit, where he was chief editor of the Detroit Post. The following year, he moved to St. Louis, becoming editor and joint proprietor with Emil Preetorius of the German-language Westliche Post (Western Post), where he hired Joseph Pulitzer as a cub reporter. In the winter of 1867–1868, he traveled in Germany – the account of his interview with Otto von Bismarck is one of the most interesting chapters of his Reminiscences. He spoke against “repudiation” (of war debts) and for “honest money” (the gold standard) during the Presidential campaign of 1868.

U.S. Senator

In 1868, he was elected to the United States Senate from Missouri, becoming the first German American in that body. He earned a reputation for his speeches, which advocated fiscal responsibility, anti-imperialism, and integrity in government. During this period, he broke with the Grant administration, starting the Liberal Republican movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected B. Gratz Brown governor.

After Fessenden’s death, Schurz was a member of the Committee on Foreign Affairs where Schurz opposed Grant’s Southern policy as well as his bid to annex Santo Domingo. Schurz was identified with the committee’s investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the Franco-Prussian War.

In 1869, he became the first U.S. Senator to offer a Civil Service Reform bill to Congress. During Reconstruction, Schurz was opposed to federal military enforcement and protection of African American civil rights, and held nineteenth century ideas of European superiority and fears of miscegenation.

In 1870, Schurz helped form the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed President Ulysses S. Grant‘s annexation of Santo Domingo, and his use of the military to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in the South under the Enforcement Acts. Schurz lost the 1874 Senatorial election to Democratic Party challenger and former Confederate Francis Cockrell. After leaving office, he worked as an editor for various newspapers. In 1875, he assisted in the successful campaign of Rutherford B. Hayes to regain the office of Governor of Ohio. In 1877, Schurz was appointed Secretary of the Interior by Hayes, who had been by then been elected President of the United States. Although Schurz honestly attempted to reduce the effects of racism toward Native Americans and was partially successful at cleaning up corruption, his solutions towards American Indians “in light of late twentieth-century developments”, were repressive. Indians were forced to move into low quality reservation lands that were unsuitable for tribal economic and cultural advancement. Promises made to Indian chiefs at White House meetings with President Rutherford B. Hayes and Schurz were not always kept.

In 1872, he presided over the Liberal Republican Party convention, which nominated Horace Greeley for President. Schurz’s own choice was Charles Francis Adams or Lyman Trumbull, and the convention did not represent Schurz’s views on the tariff. Schurz campaigned for Greeley anyway. Especially in this campaign, and throughout his career as a Senator and afterwards, he was a target for the pen of Harper’s Weekly artist Thomas Nast, usually in an unfavorable way. The election was a debacle for the Greeley supporters. Grant won by a landslide, and Greeley died shortly after the election.

Secretary of the Interior

In 1876, he supported Hayes for President, and Hayes named him Secretary of the Interior, following much of his advice in other cabinet appointments and in his inaugural address. In this department, Schurz put in force his theories in regard to merit in the Civil Service, permitting no removals except for cause, and requiring competitive examinations for candidates for clerkships. His efforts to remove political patronage met with only limited success, however. As an early conservationist, he prosecuted land thieves and attracted public attention to the necessity of forest preservation.

During Schurz’s tenure as Secretary of the Interior, there was a movement, strongly supported by Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the War Department. Restoration of the Indian Office to the War Department, which was anxious to regain control in order to continue its “pacification” program, was opposed by Schurz, and ultimately the Indian Office remained in the Interior Department.

The Indian Office had been the most corrupt of the Interior Department. Positions therein were based on political patronage and were seen as granting license to use the reservations for personal enrichment. Schurz realized that the service would have to be cleansed of such corruption before anything positive could be accomplished, so he instituted a wide-scale inspection of the service, dismissed several officials, and began civil service reforms, whereby positions and promotions were to be based on merit not political patronage.

Schurz’s leadership of the Indian Affairs Office was not uncontroversial. While certainly not an architect of the campaign to push Native Americans off their lands and into tribal reservations, he continued the practice of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of resettling tribes on reservations. In response to several nineteenth-century reformers, however, he later changed his mind and promoted an assimilationist policy.